Yes, AI Is Creating Jobs. No, That’s Not (all) Good News

The not-so-glamorous side of new AI jobs

Want to hear something terrifying? Goldman Sachs predicts that 300 million jobs will be automated, while McKinsey's estimate is even higher, ranging from 400 to 800 million.

But I already had my own “oh no” moment years before I read these predictions. That moment came when I realized that 3D models that I’ve been crafting for 10 years are just slightly better than the ones made by AI. To make things worse, it would take me a 3-4 days to make a decent 3D model. AI needed just minutes. That’s when it hit me: AI automating jobs isn’t a distant, scary possibility. It’s already happening. When I read about Klarna's CEO, who replaced 700 workers with AI and Dukaan’s CEO, who bragged about automating 90% of its workforce - I knew my suspicions were confirmed.

“But don’t worry” - said every CEO of every AI company. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman claims job losses aren’t a concern because “AI will create better jobs”, while Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei says “we lack the imagination to envision the 10,000 new roles AI could generate.” Phew, I guess we can all just breath and relax. Right?

Well, not really. AI has indeed created new jobs, but my research revealed a disturbing truth: most of them not as wonderful as we’ve been led to believe.

The Rise of "Invisible" AI Worker

The 2023 World Economic Forum predicted three new AI-driven job categories: Trainers, Explainers, and Sustainers. Take Trainers, for example. Most people think of them as genius Machine Learning Engineers working in fancy San Francisco offices, commanding six-figure salaries. Explainers, the AI product managers, supposedly enjoy similar perks. And then there are the Sustainers, the prompt engineers who've become the stuff of legend. Find the right words to whisper to ChatGPT, and you can earn $300k a year, no degree required! Just watch a few YouTube videos and you're good to go. However, this glamorous image doesn’t reflect the true (or whole) reality of new AI jobs.

Let’s look at “other” types of AI workers that companies prefer to keep away from our eyes.

Mercy

Mercy, a data labeler in Nairobi, Kenya, owes her job to AI. She and her team review flagged content on Facebook to ensure it meets Meta’s guidelines. One day, a video flagged by multiple users revealed a fatal car crash—the victim was her grandfather. Though her manager gave her the next day off, Mercy was expected to finish her shift since she was already at work. As the day went on, more users flagged the same video, forcing her to relive her grandfather’s death repeatedly, from multiple angles.

This story isn’t a product of my imagination (although I wish it was). It’s one of many stories from Feeding the Machine, a book documenting the lives of workers that contribute to AI. Mercy is among countless workers who endure daily exposure to graphic violence—murders, rapes, and violence—just to keep their jobs.

Paradoxically, while stories like Mercy’s receive little attention compared to new model releases or CEO blog posts, they reflect the reality for most workers in the AI industry. As the authors of Feeding the Machine explain:

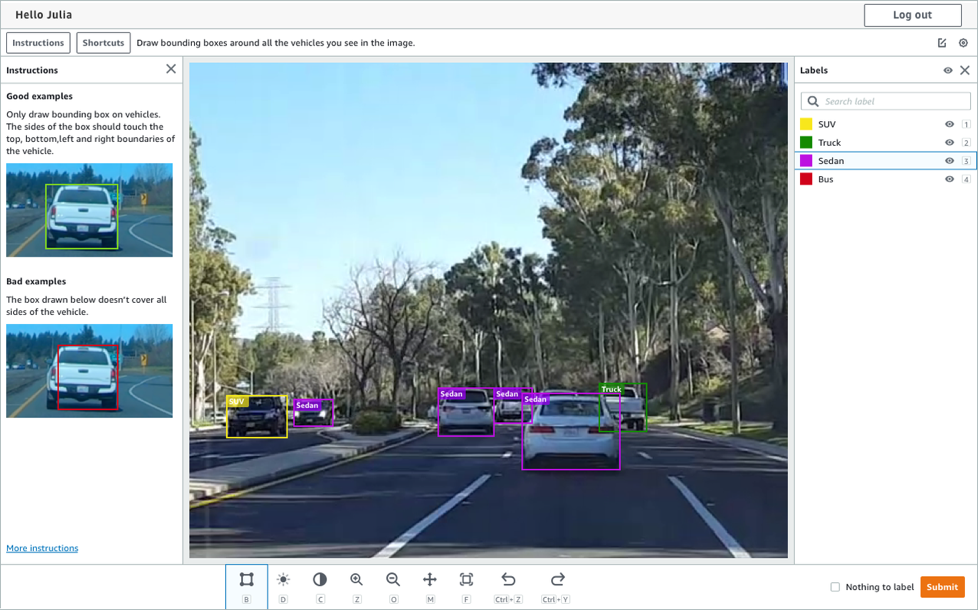

“When we think about the world of AI development our minds naturally turn to engineers working in sleek, air-conditioned offices in Palo Alto or Menlo Park. What most people don’t realize is that roughly 80 per cent of the time spent training AI consists of annotating datasets.”1

Workers like Mercy play a critical role, yet their contributions are deliberately kept “invisible.” Researchers Mary Gray and Siddharth Suri coined the term “Ghost Work” to describe this labor: “It’s meant to call out work conditions where the value of the person providing that service is literally erased.” Also known as “microwork”, it involves repetitive, low-skill, and often psychologically damaging tasks performed by workers like Mercy—tasks that represent 80% of the effort required to train AI models, yet go unrecognized.

How is it possible to hide the labor of millions building AI systems?

AI companies are strategic in creating distance between their San Francisco offices and workers like Mercy. They don’t hire microworkers directly. Instead, they rely on Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) companies, often headquartered in San Francisco but operating in the Global South. These BPOs handle data annotation, content moderation, and reinforcement learning feedback.

Daniel

Sama, the most (in)famous BPO, was founded in 2008 by the late Leila Janah as a mission-driven project to end poverty by providing jobs in developing countries. It secured contracts with tech giants like Microsoft, Google, and Facebook, offering data annotation and content moderation services—even helping OpenAI make ChatGPT “less toxic.” Sama branded itself as an “ethical AI” company, claiming to lift 50,000 people out of poverty. Yet despite the initial optimism, rumors of harsh working conditions in Kenya began to surface.

In 2022, these rumors were confirmed when Sama faced a lawsuit. Daniel Motaung, a former content moderator from South Africa, alleged the company engaged in human trafficking by luring workers from entire Africa with misleading job ads. Employees, he claimed, earned as little as $1.50 per hour to view traumatic content—child sexual abuse, bestiality, murder, suicide, torture—without adequate mental health support. Motaung developed PTSD, leaving him struggling to find new work. But what exactly was Daniel’s job?

Microwork in AI involves repetitive tasks like data labeling (tagging objects in images or analyzing text sentiment) and content moderation (filtering toxic or violent posts). One blog I encountered during this research quite appropriately states that “content moderation is not just a job, it’s a daily confrontation with the darker sides of humanity.” That is exactly what Daniel did daily.

Most microworkers are based in the Global South—countries like Kenya, Uganda, Venezuela, and the Philippines—where lax regulations and low wages attract AI companies. Work can be moved globally, from one country to another, overnight. This fuels a “race to the bottom” as companies compete to cut costs - by additionally lowering worker’s (already low) wages. One of the main reasons why most of these countries struggle so much with poverty is pretty straightforward - their colonial history. Even though none of them fully recovered from this period, they’re already being recolonized, but this time instead of gold, sugar, and enslaved people, what gets extracted is “labour, critical minerals and data of populations in peripheral countries.”2

Microworker’s median hourly wage is around $1.77, with no career advancement opportunities. Those employed through BPOs often get basic short-term contracts, while platform workers on Mechanical Turk or Appen don’t even get that much. Instead, they work in isolation, without feedback or job security. As a cherry on the top, they spend around 8.5 hours weekly on unpaid tasks like searching for gigs. 3

So I was wondering, what did AI companies do anything to address these depressing problems? Well, as it turns out not really. OpenAI distanced itself from Sama’s controversies, shifting blame for pay and mental health issues onto the BPO. One could argue that the whole reason why data annotators aren’t employed directly by OpenAI is PRECISELY because the company wants to distance itself from accountability for these jobs. There’s no transparency about how their best models are trained or where the data comes from (so much for “Open” in OpenAI). While Sama has stopped working with OpenAI on graphic content moderation, company’s CEO, Sam Altman, seems unconcerned, focusing instead on a future where “all data will be synthetic.”

Is there a solution? And what would that solution look like?

Artificial Intelligence fueled by humans

Ethan Mollick, in his 2023 Substack article, observes that “automation has always been about eliminating work that is repetitive, and often dangerous or boring.” The expectation was that AI would follow this pattern, freeing us from boring mental labor. Ironically, AI is doing the opposite right now - it’s generating a massive amounts of monotonous tasks such as tagging images and text, instead of eliminating it.

Now, to be fair, AI is creating some jobs that sound cool. Robotics Engineers, AI Ethicists, Computer Vision Engineers, LLM researchers—the list goes on. I've even seen people launch successful AI startups. But what nobody likes to admit is that these opportunities are out of reach for majority of us, as they’re concentrated in a handful of wealthy, technologically advanced countries.It's a cruel irony that it’s the labor of data annotators in the Global South that fuels the very AI companies accumulating wealth and power in places like Silicon Valley or Tel Aviv.

In Atlas of AI, Kate Crawford argues that when we think of AI, we focus on the “artificial” part—images of robots, neural networks, and algorithms pop in our minds. Yet, she writes, “AI is neither artificial nor intelligent. Rather, it is embodied and material, made from natural resources, fuel, and human labor.”4 It’s a machine powered by extracted minerals, human labour, and collective intelligence. Unfortunately, “the greatest benefits of extraction have been captured by the few.”5

Luckily, some workers are already fighting for better rights. For example, Writers Guild of America is the probably most successful case of workers making sure that their jobs are enhanced by AI, not replaced by it. Meta is being sued by some 186 content moderators in Kenya in spite or companies attempts to play “legal tricks to delay the case”. Initiatives like the Fairwork Project aim to protect microworkers by rating platforms on transparency and working conditions.

So no, I don’t believe the solution to these problems is to pause all AI development. I’d like to see AI as a tool that enhances us instead of exploiting us, and where the benefits are shared across all of humanity. I also believe that the path to this future begins with acknowledging the invisible workers that build it and ensuring that their labor is valued and properly compensated for, not just extracted.

James Muldoon, Mark Graham, Callum Cant, Feeding the machine (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024), 30

Muldoon, Graham, Cant, Feeding the machine, 216

Muldoon, Graham, Cant, Feeding the machine, 31

Kate Crawford, Atlas of AI (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 8

Crawford, Atlas of AI, 28